A new, more transmissible form of the virus is driving a rapidly spreading Mpox outbreak in Africa, which the continent’s health agency called an emergency on Tuesday.

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security for the deadly disease.

Experts from the World Health Organisation will also gather on Wednesday to decide whether to sound the United Nations agency’s highest warning.

If the WHO declares a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, it will be the second time since the virus expanded globally in 2022.

But the new outbreak, which has been crossing borders from its epicentre in the Democratic Republic of Congo to other African nations, is being driven by a new strain of the virus which has alarmed health experts.

Here is what you need to know.

– What is mpox? –

The infectious disease formerly known as monkeypox was first detected in humans in the DRC in 1970.

There are two subtypes of the virus: clade I and clade II.

The deadlier clade I has been endemic in the Congo Basin in central Africa for decades.

Meanwhile, the less severe clade II has been endemic in parts of West Africa.

Until the last few years, outbreaks were mostly sparked by people catching the virus from infected animals such as rodents, for example when eating bushmeat.

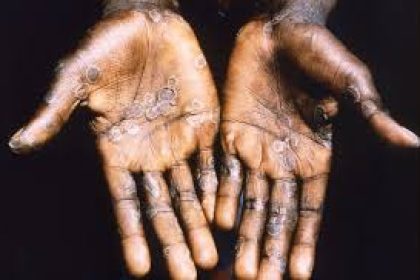

Symptoms include fever, muscular aches and large boil-like skin lesions.

– The global outbreak? –

The virus rose to greater prominence in May 2022, when a new less-deadly strain called clade IIb spread across the world, mostly affecting gay and bisexual men.

The WHO declared a PHEIC in July 2022 which lasted until May 2023.

Between January 2022 and June 2024, 208 deaths and more than 99,000 mpox cases were recorded across 116 countries, according to the WHO.

– The new strain? –

Unlike the 2022 global outbreak, the latest surge has been driven by the deadlier clade I — as well as its new mutated variant.

The new strain, called clade Ib, was first detected among sex workers in the remote mining town of Kamituga in the DRC’s South Kivu province in September 2023.

Unlike previous outbreaks in the central African country, the new strain has been partly driven via sexual transmission, including between heterosexuals, researchers have said.

It has also been recorded spreading through non-sexual contact between people, including children playing together at school.

Clade Ib causes death in around 3.6 per cent of cases, though infants and children are more at risk, according to the WHO. It also causes more severe disease than clade II.

Almost all of the DRC’s provinces are now affected by either clade I or clade Ib; a researcher at the University of Rwanda studying the outbreak, Jean Udahemuka, told AFP.

Udahemuka has previously said that clade Ib is “undoubtedly the most dangerous strain” of mpox so far.

– Where is affected? –

More mpox cases were reported in the first half of this year than in all of 2023, according to WHO figures.

Between January 2022 and August 4, there were 38,465 cases of mpox and 1,456 deaths in Africa, according to the Africa CDC.

The majority of the recent cases have been in the DRC.

But over the last month, Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda all reported their first-ever mpox cases.

Clade Ib has been detected in all four countries, none of which have reported deaths, according to the WHO.

– Vaccines? –

During mpox’s global spread in 2022, vaccines were quickly deployed in wealthier regions such as Europe and North America which helped bring the outbreak under control.

But the available vaccines have largely not been made available in the African countries most affected by mpox.

On Tuesday, Africa CDC head Jean Kaseya announced an agreement with the European Union and pharma firm Bavarian Nordic to supply and distribute 200,000 mpox vaccine doses across the continent.

Kaseya acknowledged that the doses of Bavarian Nordic’s mpox vaccine — which requires two shots per person — would not be enough.

But there is a plan to secure 10 million vaccine doses for Africa, he told an online media briefing.

Kaseya also emphasised that if Africa had received the necessary vaccine doses and support earlier, then case numbers would not be so high now.